Fitch warns sovereign credit risk will rise with worsening climate events

Fitch Ratings warns that global sovereign credit ratings will get downgraded by several notches in the coming years as climate change damage balloons and transition from fossil fuels weighs on the most exposed countries.

The Climate Crisis is accelerating. The IPCC says that the Paris Agreement goal of keeping temperature increases to less than 1.5°C-2°C above the pre-industrial benchmark has already been missed and temperature increases are on course to reach a catastrophic 2.7C-3.1C by 2050. At that point extreme temperature events will become routine and large parts of the world will become uninhabitable.

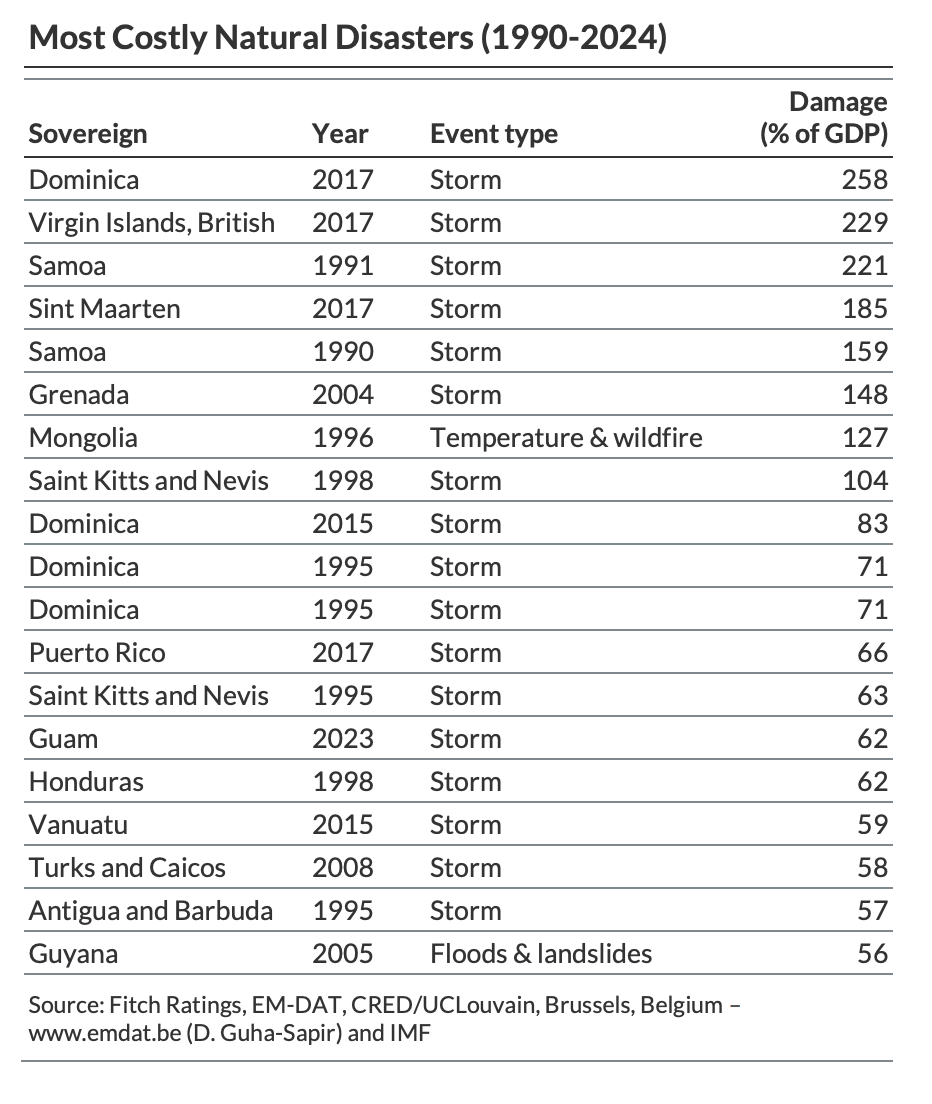

An annual disaster season is now well established that brings bigger floods, increasingly powerful hurricanes , destructive wildfires and most recently the big freeze that has buried northern countries under record snow coverage. The damage done each year is rising exponentially and starting to run into the trillions of dollars. Insurance companies are being forced to reassess their policies as costs rise and the demand for catastrophe bonds is soaring.

In a research note released in January 2026, Fitch said that “climate-related risks are increasingly likely to affect sovereign ratings over the medium term,” particularly for emerging markets and highly exposed economies.

“Sovereigns are already experiencing growing costs from climate hazards,” the report stated, pointing to a rise in climate-related natural disasters and the increasing scale of government support packages. Fitch highlighted that these developments are accelerating faster than anticipated: “The scale of weather-related events and policy transitions is likely to exceed prior baseline assumptions.”

Fitch has developed a Sovereign Climate Vulnerability Index (SCVI), which identifies 23 of the 125 rated sovereigns as highly vulnerable to climate risk. “Small island developing states and frontier markets are among the most exposed,” the report noted, warning that fiscal pressures from adaptation and recovery spending are particularly pronounced for these countries.

The agency also raised concerns about the uneven pace of transition risk across developed and emerging economies. “Advanced economies tend to be better positioned to absorb the economic costs of decarbonisation,” analysts wrote. “Emerging markets face sharper trade-offs between growth, energy access and emission targets.”

Although sovereign ratings have so far been “resilient to climate-related events,” Fitch indicated that this resilience may weaken as frequency and severity increase. “Rating downgrades are more likely where exposure is high and policy responses are insufficient or delayed.”

Carbon-intensive economies that delay transition planning may also face rising financing costs. “Longer-term investor perception of climate risk will influence funding conditions,” Fitch wrote, particularly in light of evolving ESG mandates across global capital markets.

Fitch concluded that sovereigns unable to mitigate or adapt to rising climate risks may experience a deterioration in creditworthiness. “Climate-related shocks will become more relevant for ratings when they lead to sustained output losses, fiscal weakening or heightened political instability,” the report said.

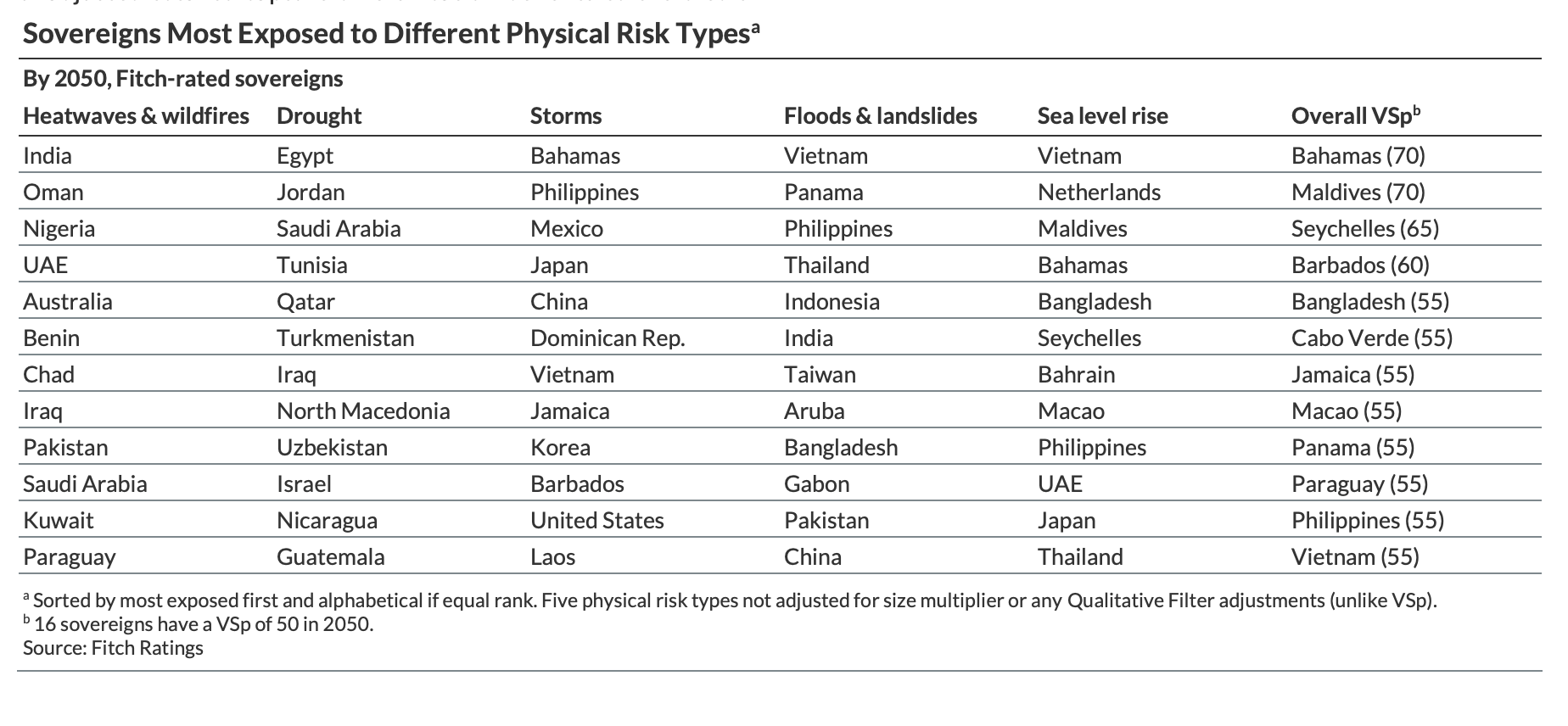

All sovereigns are likely to face additional costs from the transition to clean energy and from physical climate risks. Around half of Fitch-rated sovereigns have a Climate.VS of 50 or more by 2050, signalling that climate-related factors could be sufficiently material to lead to a downgrade by then. But only 6% have a Climate.VS of 70 in 2050, indicating a potential downgrade of three notches.

Particularly exposed are Angola, the Bahamas, Gabon, Iraq, the Maldives, Mozambique and Republic of Congo (all VS 70).

“We expect the impact to build up more rapidly and substantially between 2035 and 2050 as global demand for fossil fuels declines, global temperatures rise and extreme weather events become more frequent and severe,” Fitch said.

The agency plans to integrate SCVI findings more explicitly into its sovereign rating methodologies over time.

Nevertheless, these are long-term risks. Risks out to 2035 are the main focus of whether climate should lead to downgrades today. In 2035, the highest Climate.VS result is 50, indicating a potential downgrade of just one notch in the next 10 years, other things equal, and this is for just 7% of Fitch’s rated portfolio. Fitch identifies five physical risks: heatwaves and wildfires, droughts, storms, floods and landslides, and sea level rise.

“We expect the impact to build up more rapidly and substantially between 2035 and 2050. This reflects the expected decline in global demand for fossil fuels and the increase in physical risk as global temperatures rise and extreme weather events become more frequent and severe,” Fitch says.

Unlock premium news, Start your free trial today.