$23bn windfall for Kazakhstan as Beijing shifts up a gear on New Silk Road

Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is undergoing a transformation in both scale and geography. This is occurring amid complexities brought about by US President Donald Trump's tariffs and issues with chronic overcapacity versus the market in China’s metals processing. Kazakhstan increasingly finds itself standing at the centre of this shift.

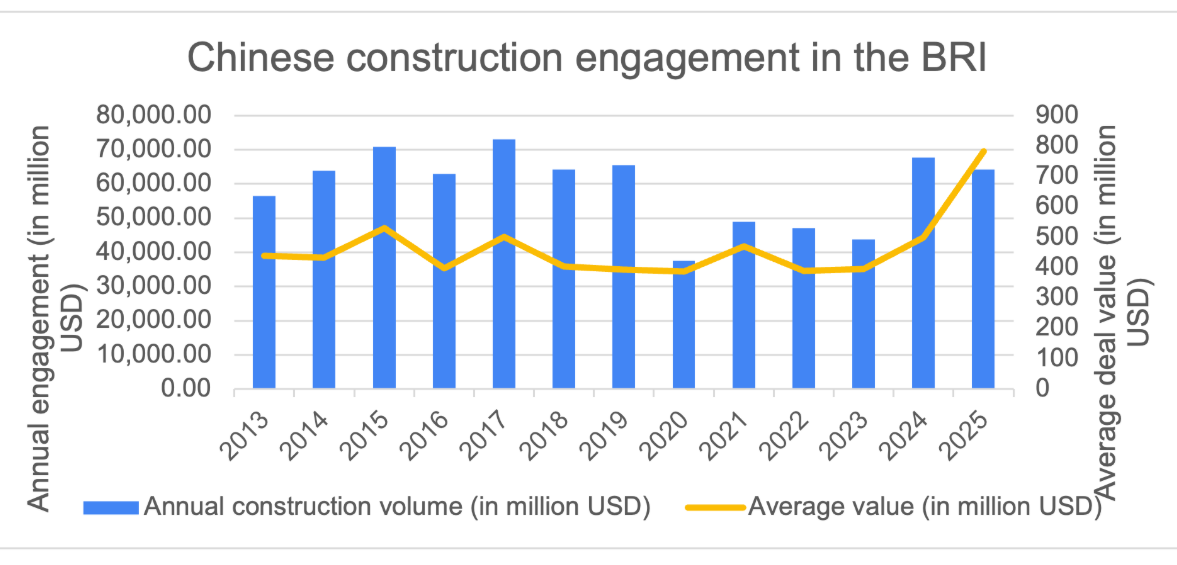

In the first six months of this year alone, Chinese companies committed to a record $124bn in new projects across countries participating in BRI, according to a report by Australia’s Griffith Asia Institute. Made up of $66.2bn in construction contracts and $57.1bn in investments, the figure surpasses the $122bn registered over the entirety of 2024. And it is a surge under BRI (also known as One Belt One Road (OBOR), the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road, or just the New Silk Road) that illustrates the way in which Beijing is reorienting its overseas engagement towards resource security and industrial capacity at a time of international trade frictions and global supply uncertainty.

The fact that these spheres often lead to megaprojects “is bucking the [Beijing] ambition to have ‘small yet beautiful projects’ in the BRI propagated through official channels,” observes Griffith, adding: “However, it is important to note… that most large infrastructure projects are resource-backed deals (e.g., oil, gas) rather than fiscal spending deals (e.g., road construction), with relatively low financial risks for Chinese counterparts.”

Chinese President Xi Jinping met his Kazakh counterpart Kassym-Jomart Tokayev at the Second China-Central Asia Summit held in Astana in June (Credit: yidaiyilu.gov.cn).

The composition of the BRI spending points to a sharp upturn in favour of energy and metals. Chinese oil and gas projects reached $30bn in the first half of the year. They include a $20bn gas processing park in Nigeria, according to the Griffith Asia Institute report. Green energy, long a showcase sector for BRI, registered almost $10bn in new commitments. That’s the highest ever such figure recorded in a half-year period.

But perhaps the most dramatic expansion came in metals and mining. With nearly $25bn committed to aluminium and copper ventures, Chinese entities have invested more in the sector in six months than in any previous full year, the report said. This reflects not only Beijing’s appetite for critical raw materials (CRM), but also pressures posed by overcapacity at home and the challenges of rising tariffs in key export markets.

Looking at investment models currently favoured by Chinese companies pursuing BRI projects, Griffith assesses that “when comparing construction and investment in different sectors, it becomes clear that in mining and technology, Chinese firms are increasingly prioritising equity investments, despite the higher risks involved; meanwhile, energy investments continue to be dominated by construction deals rather than equity-based investments”.

What makes 2025 especially noteworthy for BRI so far is the geographic distribution of the capital. While earlier waves of BRI emphasised the Middle East, South Asia and maritime corridors in East Asia, the current capital surge shows a decisive pivot into Central Asia. Resource-rich Kazakhstan, in particular, has emerged as the standout destination for Chinese investment.

In January to June alone, Central Asia’s largest economy attracted an estimated $23bn in BRI-linked commitments, making it the single largest capital recipient worldwide, according to figures cited by the Griffith Asia Institute. To put this into perspective, the next highest recipients—Thailand with $7.4bn and Egypt with $4.8bn—pale in comparison to the scale of Chinese engagement in Kazakhstan.

"Green" aluminium production chain

This inflow of investment from China includes a $12bn plan by the privately held East Hope Group, one of China’s largest aluminium producers, to create an integrated “green” aluminium complex in Kazakhstan’s Kostanay and Aktobe regions, the China Global South Project reported in August. This undertaking is designed not as a simple extraction venture, but as a vertically integrated industrial hub that spans the entire aluminium production chain.

East Hope’s blueprint involves developing 11 deposits of bauxite and coal, constructing a mining and processing plant capable of handling 6mn tonnes of ore annually, and building a smelter that can produce 3mn tonnes of aluminium per year once fully operational, China Global South Project’s report said. Supporting this industrial ecosystem will be a massive 4.5-gigawatt power station.

The project, which is being marketed as environmentally sustainable thanks to its circular-economy design, is expected to provide employment for over 10,000 people at its peak. Phase one alone envisions the processing of 2mn tonnes of alumina and the smelting of 1mn tonnes of finished aluminium annually, with subsequent stages expanding capacity to the full planned scale by 2030, Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Industry and Construction said in a statement.

This aluminium complex demonstrates a dual rationale behind China’s industrial push in BRI countries. On the one hand, it reflects the domestic reality of a saturated aluminium sector in China, where years of rapid expansion have led to chronic overcapacity, depressed prices and thin margins, the China Global South Project argues. Relocating production abroad provides a release valve for this surplus capacity.

On the other hand, it serves as a strategic manoeuvre to evade rising trade barriers, the report posits. Chinese aluminium has been subject to increasingly punitive tariffs in the US, the EU and elsewhere, the report notes. By producing aluminium in Kazakhstan, Chinese companies can rebrand exports as Kazakh rather than Chinese, thereby sidestepping restrictions and maintaining competitiveness in key markets.

For Kazakhstan, the attraction is obvious: instead of simply exporting raw input bauxite, the country secures foreign capital to build domestic processing and manufacturing capacity, gaining jobs, technology and industrial expertise in the process. This is line with the Kazakh government’s long-running aim to switch to value-added production instead of simply exporting raw materials.

Copper another pillar of engagement

If aluminium is one pillar of this deepening engagement, copper is the other. In the first half of 2025, Chinese investments in Kazakhstan’s copper industry totalled some $7.5bn, with the flagship project a $1.5bn smelting complex planned for near the Aktogai deposit in Abai Region. Led by the state-owned China Nonferrous Metal Industry’s Foreign Engineering and Construction Company (NFC), this initiative represents a full-fledged industrial cluster. The new smelter, designed to handle 300,000 tonnes of copper annually, will be tightly integrated with some of Kazakhstan’s largest copper mines, operated by Kazakhmys and KAZ Minerals.

The facility will produce not only copper cathode but also valuable byproducts such as refined gold, silver and sulfuric acid. Scheduled to begin operations by 2028, the project is expected to employ more than 1,000 workers and position Kazakhstan as a significant hub for copper refining as well as mining.

Globally, copper supply has tightened due to setbacks in Chile and Peru, which traditionally dominate global production, China Global South Project noted in a separate report. At the same time, China’s own smelting sector has expanded so aggressively that refiners are facing acute shortages of concentrate feedstock. Treatment and refining charges—the fees smelters receive for processing ore—have fallen to unsustainable lows, forcing producers to consider output cuts.

By investing directly in Kazakhstan, China not only secures a reliable stream of ore, it also relocates some of its overbuilt smelting capacity to a more favourable jurisdiction. For Kazakhstan, the upside mirrors that of the aluminium deal: rather than exporting unprocessed ore, the country gains value-added industries and the chance to climb higher up the global supply chain.

China’s investment drive in Kazakhstan is beginning to move beyond aluminium and copper, extending into other strategically important minerals. The country holds significant reserves of CRM, and the government in Astana has been actively encouraging new projects in these areas.

In early 2025, officials announced the launch of exploration programmes for lithium at the Akhmetkino deposit, along with fresh initiatives in tungsten. A German company has already committed $8mn to develop the Akhmetkino lithium site, with the possibility of expanding its investment to as much as $500mn if commercially viable reserves are confirmed, The Astana Times reported.

At the same time, Kazakhstan has been expanding its tungsten industry, having inaugurated a $300mn processing facility in November 2024. It is preparing new mining operations to feed it.

These developments have not gone unnoticed in Beijing, where Chinese companies—driven by their own ambitions in the battery supply chain and rare metals—have shown growing interest in participating in Kazakhstan’s lithium and tungsten sectors.

Risk of dependence

On the one hand, the arrival of this capital from China bodes well for Kazakhstan, as the government in Astana has made it clear in recent years that foreign investors must go beyond extraction and commit to on-site processing, joint ventures and technology transfer. Both the East Hope aluminium complex and the NFC copper smelter were structured with these conditions in mind. They are not merely mines but integrated industrial ecosystems designed to create jobs, infrastructure and local expertise. Officials have touted them as evidence that Kazakhstan can leverage global demand for resources to drive its own economic diversification.

On the other hand, long-term dependence on one dominant partner for investment will inevitably come with risks. China’s overwhelming role as Kazakhstan’s top source of foreign investment could potentially limit Astana’s bargaining power in the long run.

The Griffith report predicts that the trend in BRI investment growth in Kazakhstan will continue through the rest of 2025, with sustained investment in mining, green energy and advanced manufacturing. Only time will tell whether Kazakhstan will successfully balance its investment and capital partnerships.

In the wider conclusions at the end of the report, Griffith forecasts “for 2025, a further expansion of BRI investments and construction contracts seems possible despite (or because of) global economic headwinds driven by US-led trade impositions.

“On the one hand, there is a clear need for investments to green boost growth to support the green transition, both in China and in BRI countries. This provides continued opportunities for mining and minerals processing deals, technology deals (e.g., EV manufacturing, battery manufacturing) and green energy (e.g., energy production and transmission). China refers to these industries (electric vehicles, batteries and renewable energy) as the ‘New Three’.

“Furthermore, global trade volatilities and uncertainties can spur investments in supply chain resilience and exploration of new markets by Chinese companies. However, risks emerge due to the uncertainty of possible activities by global financial institutions with strong US board presence (e.g., World Bank Group, Asian Development Bank), while China-dominated development banks (e.g., AIIB, NDB) should provide infrastructure development opportunities for Chinese contractors.

“Nevertheless, we do expect Chinese BRI engagement to reach lower levels in the second half of 2025 with fewer megadeals.

“In line with our previous predictions, we continue to see deal numbers increasing. With strong engagement in sectors requiring significant investment (e.g., mining, manufacturing), compared to sectors with variable engagement (e.g., renewable energy), we can expect deal size to also remain larger than in 2022 and 2023.”

* The author of the Griffith report is Dr Christoph Nedopil, Director of the Griffith Asia Institute and a Professor at Griffith University in Brisbane, Australia. He is also a Visiting Professor at FISF Fudan University, Shanghai, Acting Director of the Green Finance & Development Center at FISF Fudan University, and a Visiting Faculty at Singapore Management University (SMU).

Unlock premium news, Start your free trial today.

_and_US_Ambassador_to_Kyrgyzstan_Lesslie_Viguerie_(center)__050226.jpg)