New trade routes in a fractured world

US President Donald Trump has upended the liberal world order that promoted free trade agreement and cooperation, for a more selfish protectionist “me first” mindset. Trump is actively dismantling the rules-based international order, restricting competition and turning tools like tariffs into political weapons. As part of an new economic paradigm that is a return to a pre-world war imperialistic transactional approach he is also trying to divide the world into spheres of influence again as part of his updated Monroe Doctrine outlined in his National Security Strategy released at the end of last year.

The result is a scramble to diversify away from US trade. In her speech announcing what she called the “mother of all trade deals” with India in January, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said the motivation was that “trade has been weaponised”.

After 20 years of negotiation, the EU suddenly felt compelled to close the agreement, which will slash duties on Indian imports and pry open a long-protected market. Brussels feels exposed to the increasingly unpredictable US, Europe’s biggest trade partner, accounting for 20% of exports and $4.5 trillion in annual trade.

In the same week, the EU also moved to finalise a near-identical deal with Mercosur in Latin America, likewise decades in the making. Neither deal offsets reliance on the US market, but both mark the start of a long process to spread risk and diversify global business.

However, the process started well before Trump took office. After two decades of prosperity fuelled by “globalisation” following the collapse of the socialist experiment in 1991, the “rise of the rest” reached a point at the start of this decade where tensions between east and west were starting to grow as countries like Russia and China began to flex their economic muscles.

That led a fractured world where smaller countries began to coalesce into groups in either the US-led or China-led camps. This process was accelerated by the global pandemic in 2020 when companies suddenly had to shorten supply chains and reshoring operations. Trump has only catalysed a breaking up of global trade that was already well underway, amply illustrated by the slow death of the WTO, which at one point a decade ago was supposed to be regulator of globalised trade, but today is totally dysfunctional.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and ensuing sanctions further redirected investment into new Eurasian trade routes. The Middle Corridor, linking Europe and East Asia via Central Asia and the Caucasus while skirting Russia’s southern flank, has gained prominence. Trump has only catalysed a fragmentation of global trade that was already underway, illustrated by the slow decline of the WTO, once the regulator of globalised trade, now largely paralysed.

South-South trade grows

As bne IntelliNews has reported, the Global South is now rapidly forming alternatives to the Western-led global order, which Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin has criticised as the “unipolar” world – a US hedgemony. In their alternative multipolar world order, Global Emerging Markets Institutions (GEMIs) are being rapidly rolled out or beefed up to manage geopolitics, trade and security – new institutions that the Western powers are largely excluded from such as the BRICS+ or G20. It’s still a work in process, but trade is already rapidly shifting to follow the contours of the new realities.

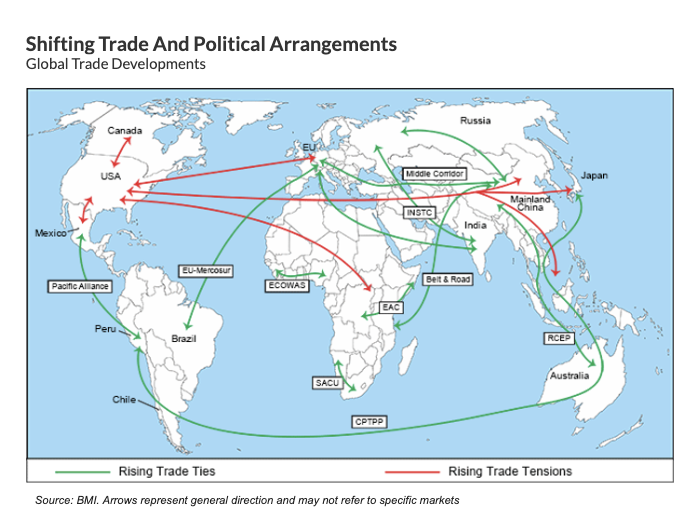

Entering 2026, trade tensions are rising between the US and its partners, while trade is on the increase within partnerships and blocs that do not include Washington, as set out in a map shared by analysts from research firm BMI in a recent webinar.

A new report from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) also says that global trade “enters 2026 under mounting pressure from slower growth, geopolitical fragmentation, accelerating digital and green transitions and tighter national regulations”.

According to UNCTAD, “These forces are reshaping trade flows, investment decisions and global value chains, with the greatest risks and opportunities concentrated in developing economies … Nearly two-thirds of global trade now occurs within value chains reshaped by geopolitics, industrial policy and new technologies.”

UNCTAD data indicates a sharp rise in South-South trade over the last three decades, from $0.5 trillion in 1995 to $6.8 trillion in 2025. More than half of Africa’s exports, for example, now go to other developing countries. The share of Brazil’s imports coming from Asia rose sharply after Trump’s tariffs were announced.

However, as UNCTAD points out, interregional trade outside Asia, particularly between Africa and Latin America, remains underdeveloped. Strengthening these linkages could become a key driver of resilience in global trade networks.

Moreover, interdependence can fuel tension as much as growth, as shown by frictions in trade within Asia. As supply chains deepen locally and governments lean on industrial policy, economies increasingly clash, not only with the US or Europe, but with one another.

India has expanded anti-dumping duties and quality controls, hitting imports from China, Vietnam and South Korea, arguing the measures protect domestic manufacturing and reduce import dependence in electronics, chemicals, and steel. China has responded with similar tools, tightening controls on critical minerals and technologies, reverberating across Japan, South Korea and Southeast Asia. Since late 2025, much of China’s trade friction has targeted Japan following Prime Minister Takaichi’s comments on Taiwan.

In Southeast Asia, Indonesia’s restrictions on raw minerals and push for onshore processing have unsettled Japan and South Korea. Thailand and Vietnam face complaints over pricing in sectors from tyres to solar panels. Even within ASEAN, competition for investment is rising.

Yet trade is still expanding in digital services, finance, tourism, EVs, batteries and semiconductors, as companies hedge risks by spreading production. Australia is warming to trade with China again, and LNG supplies to Japan have risen with the Santos gas project. Trade agreements such as RCEP and bilateral deals, including Japan-Vietnam and South Korea-Indonesia, keep channels open despite disputes.

Europe’s trade partners

As bne IntelliNews has reported, the EU has rushed to seal long-planned agreements with both India and the Mercosur bloc, while leaders of EU countries are also courting China.

After more than 20 years of negotiations, the EU and Mercosur — Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay — concluded a major trade partnership in January, creating one of the world’s largest free-trade areas, covering roughly 700mn people.

The agreement is designed to dismantle up to 91% of tariffs on European goods entering Mercosur markets and 92% of levies on South American exports to the EU. The deal will significantly expand the access of European goods and companies to the South American market and resources, including rare earths. Brussels estimates it will save European exporters over €4bn annually in duty payments.

Safeguards are included for sensitive sectors, with final approval depending on a decision by the Court of Justice of the European Union.

The EU-India free trade agreement, finalised on January 27 after two decades, cuts duties on 97% of EU exports and grants preferential access for 99% of Indian exports, while protecting sensitive sectors like European automobiles.

Leaders from both sides framed the accord as a landmark step following intensified negotiations as India and Europe sought supply chain resilience together. Under the pact, tariffs on almost all EU goods exports to India will be removed or reduced, delivering up to €4bn in annual duty savings.

India will gain improved access for textiles, leather and marine products, while lowering barriers on automobiles, and wines and spirits over time for consumers globally. The is part of India’s broader trade diversification, as New Delhi increasingly uses free-trade agreements (FTAs) and bilateral trade deals as an important tool to increase its geo-economic influence.

Crossing Eurasia

Efforts to improve transit times between Europe and East Asia across the Eurasian landmass have been underway for years, but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and subsequent sanctions have altered priorities, in particular raising the emphasis on the Middle Corridor.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) spans over 140 countries with estimated investments up to $8 trillion, linking Asia, Europe, Africa and parts of Latin America. Going far beyond trade, it covers transport, energy, industrial, urban, digital and space projects. In the first half of 2025, Chinese firms committed $124bn to BRI projects, highlighting its ongoing strategic importance, according to a report by Australia’s Griffith Asia Institute. However, while some participants have benefitted from enhanced growth, concerns have been raised about debt and governance challenges.

The Middle Corridor (Trans-Caspian International Transport Route) links western China with Europe via Central Asia, the Caspian Sea, the South Caucasus, and Turkey. Bypassing Russia and the Suez Canal, it shortens journeys by 2,500 km and cuts transit times to 10-15 days. Trade is rising quickly, spurring investment in ports, railways and logistics hubs. However, capacity, costs, and political risks remain constraints.

The International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) links the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf with Russia and northern Europe via Iran, the Caucasus and Caspian Sea. It can reduce transit times between India and Europe by 40% and freight costs by 30%. Growing cargo volumes and new agreements highlight the corridor’s rising geopolitical and economic significance.

Russia’s partners

As sanctions have reduced trade with Western countries, Russia has pivoted east, bolstering its relations with China, India and other countries from the Global South.

When Russia and China declared a “no limits” partnership in 2022, the symbolism was powerful — but the economic reality has proven very different. Despite deepening ties in energy, defence and diplomacy, the commercial relationship is now showing signs of strain across trade, investment and financial channels.

Bilateral trade surged to a record $244bn in 2024, but has since contracted by around 10% in the year to September 2025. China remains Russia’s dominant trading partner, accounting for 30% of its exports and half its imports. Yet Russia accounts for just 3% of China’s goods exports.

The strong relationship between Russia and India was highlighted by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s visit to Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India in December 2025, as Putin has broken with the West completely and taken a big bet on the Global South Century.

As bne IntelliNews reported, Putin brought a planeload of big Russian businessmen with him, with the aim of setting up Russian JVs — to find a use for the pile of rupees accumulated from Russian oil sales to India and supercharge India’s industrial and manufacturing prowess at the same time.

South-South blocs

Reflecting the increase in South-South trade, blocs uniting countries across Asia, Latin America and Africa have grown in prominence, and also attracted interest from outside the region.

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) unites 15 Asia-Pacific economies that together account for about 30% of global GDP, trade, and population. It brings together the ten ASEAN states with China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. Signed in 2020 and in force since January 2022, RCEP is widely seen as strengthening Asian supply chains and deepening intra-regional trade, while enhancing China’s economic influence. The bloc has opened to new members, with Sri Lanka advancing its accession bid in 2025.

The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) links 12 Asia-Pacific and European economies, eliminating tariffs on over 99% of goods and easing trade in services, digital commerce, and investment. The UK joined in 2024, and several other countries including Indonesia have applied or expressed interest.

Uniting Africa

Despite recent growth, trade between African countries remains modest as a share of total trade, but the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is intended to change this pattern.

It unites all 55 African Union member states and eight regional blocs. Its goal is to form a single continental market of around 1.3bn people with a combined GDP of about $3.4 trillion. As a flagship initiative of the AU’s Agenda 2063, it supports Africa’s long-term transformation and global competitiveness. AfCFTA seeks to remove trade barriers, expand intra-African trade, and promote value-added production and services. By strengthening regional value chains, it encourages investment, job creation, and industrial development. The agreement entered into force in May 2019, trading began in January 2021, and its secretariat is based in Accra, Ghana.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) is a regional bloc founded in 1975 under the Treaty of Lagos to promote economic integration, political cooperation, and stability across West Africa. Headquartered in Abuja, it unites 15 member states, with Nigeria, Ghana, and Côte d’Ivoire as its largest economies. Its mandate spans trade, transport, energy, agriculture, finance, and social policy, but progress toward a fully integrated market has been uneven, with intra-regional trade remaining low due to tariff resistance and fiscal concerns. ECOWAS has also become a key regional security actor, notably through its ECOMOG interventions in Liberia and Sierra Leone. Today, it enforces a zero-tolerance stance on military coups, threatening sanctions and intervention as instability spreads in the Sahel, where junta-led states have formed a rival bloc aligned with Russia.

The Southern African Customs Union (SACU) comprising Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Namibia and South Africa is the world’s oldest functioning customs union. Revenue-sharing is vital to smaller members. Trade represents over two-thirds of GDP, and the bloc maintains agreements with the EU, UK, MERCOSUR, Mozambique, and the US.

The East African Community (EAC) — Burundi, the DRC, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda — has strong intra-regional trade. Cross-border digital payments and plans for a single regional currency by 2031 signal growing integration and dynamism. The region has also adopted the East African Payment System (EAPS), a real-time gross settlement system designed to ease cross-border payments and facilitate trade.

Unlock premium news, Start your free trial today.