COMMENT: Uncertainty and geopolitics plague Russia’s negotiations with China on gas supply deals

China is now the only potential buyer of Russian Arctic gas and the only customer with the capacity to absorb significant amounts of gas from the Yamal Peninsula, home to some of the country’s largest reserves, Sergey Vakulenko, an independent energy analyst and consultant to a number of Russian and international global oil and gas companies said in a note for Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Prior to the war in Ukraine, the volume of gas in Yamal exceeded what Europe could absorb. “State-owned Gazprom has long sought a way to export Yamal gas to China. Low upstream costs mean it could still be a profitable trade, despite the long distances to the Chinese market,” he said.

“The distance from Yamal to Kyakhta on the Mongolian border (935km) is about the same as from Yamal to the Ukrainian border. Even if it costs about $100 per thousand cubic metres to pump gas from Yamal to China, Russian gas would still be cheaper for Chinese buyers than the alternatives,” Vakulenko said.

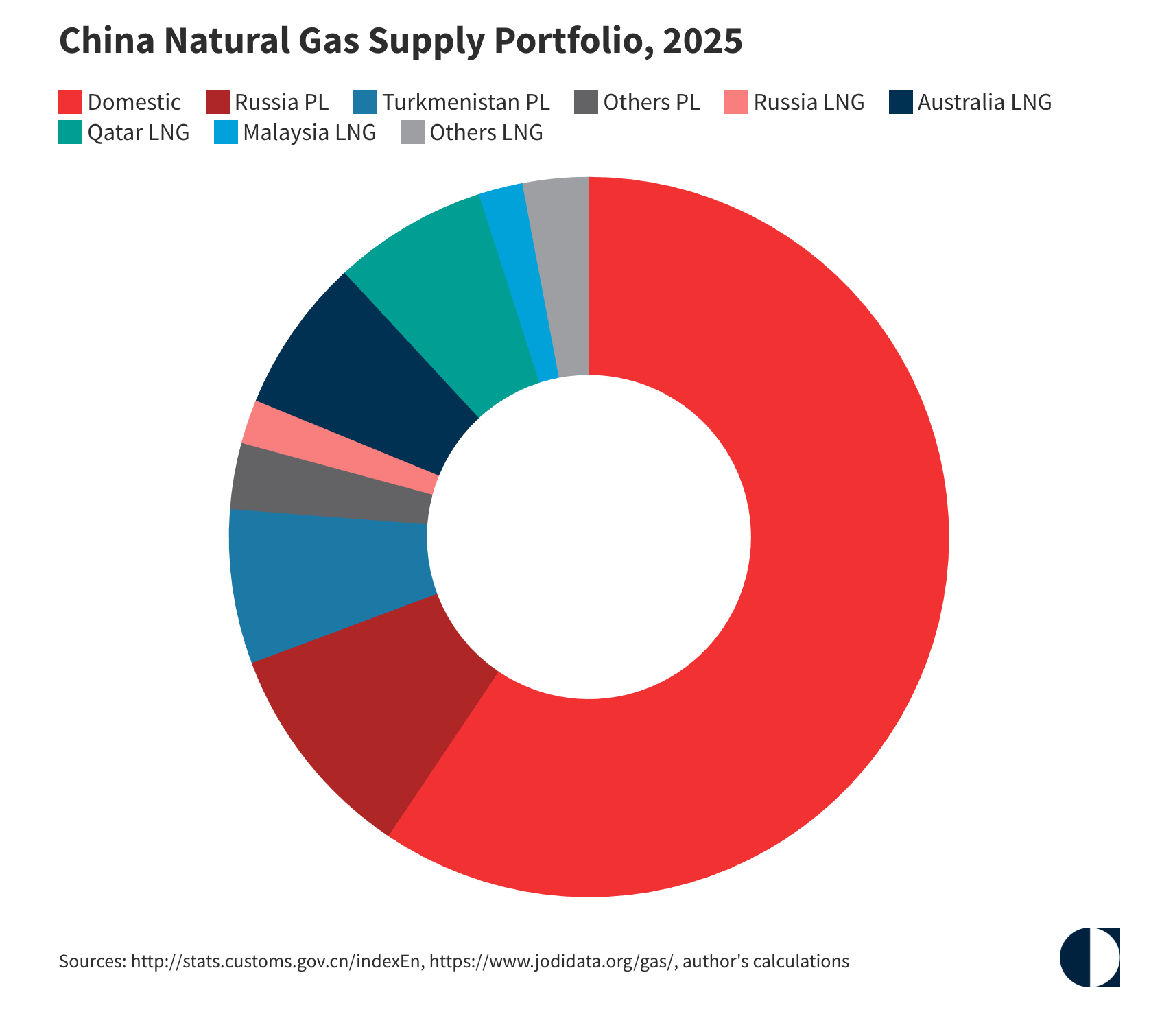

China currently consumes just over 400bn cubic metres of gas per year. Around 60% is produced domestically, while the rest is imported—half via pipeline, mostly from Russia and Turkmenistan, and half as liquefied natural gas (LNG).

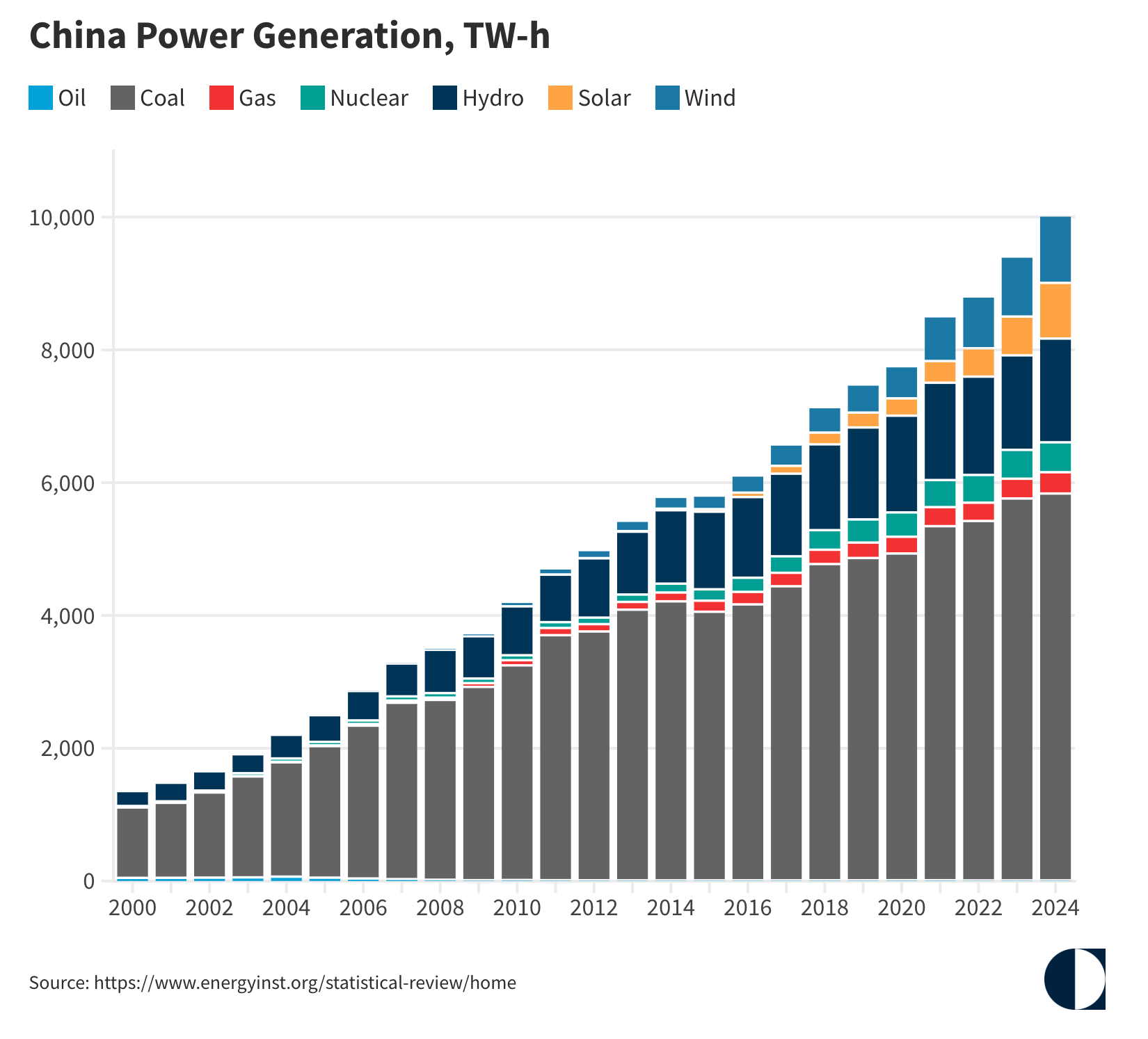

“China is a leader in renewable energy, but demand for electric power is forecasted to grow even faster. Gas makes up only a relatively small proportion of the energy China consumes. However, replacing coal with gas in electricity production cuts carbon dioxide emissions per kWh in half, and reduces air pollution (which is a priority for Beijing). China is also switching its trucks to run on LNG in order to reduce oil imports and reduce CO2 emissions,” says Vakulenko.

CNPC forecast the country’s annual demand for gas will rise to 600-670bn cubic meters by 2040. They also predict that China’s gas production will peak at about 310bn cubic meters somewhere between 2035 and 2040, leaving a widening gap for imports. “By the second half of the 2030s, China’s gas imports will grow from the current 180bn cubic metres to between 290 and 390bn cubic metres,” Vakulenko said, citing forecasts by CNPC researchers.

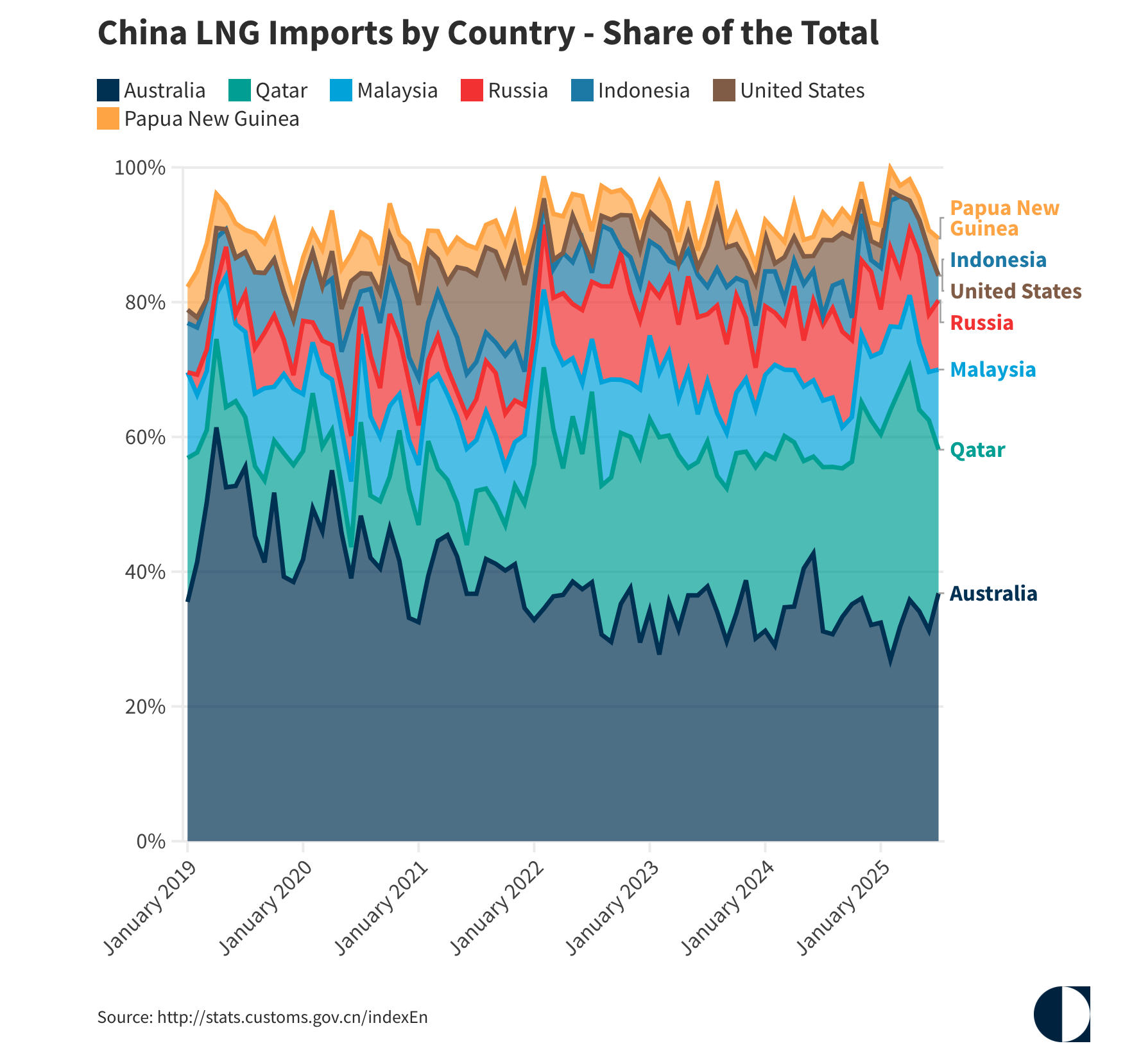

About a third of China’s LNG imports currently come from Qatar, a third from Australia, 10 percent each from Russia and Malaysia, and the remaining 15 percent from other exporters.

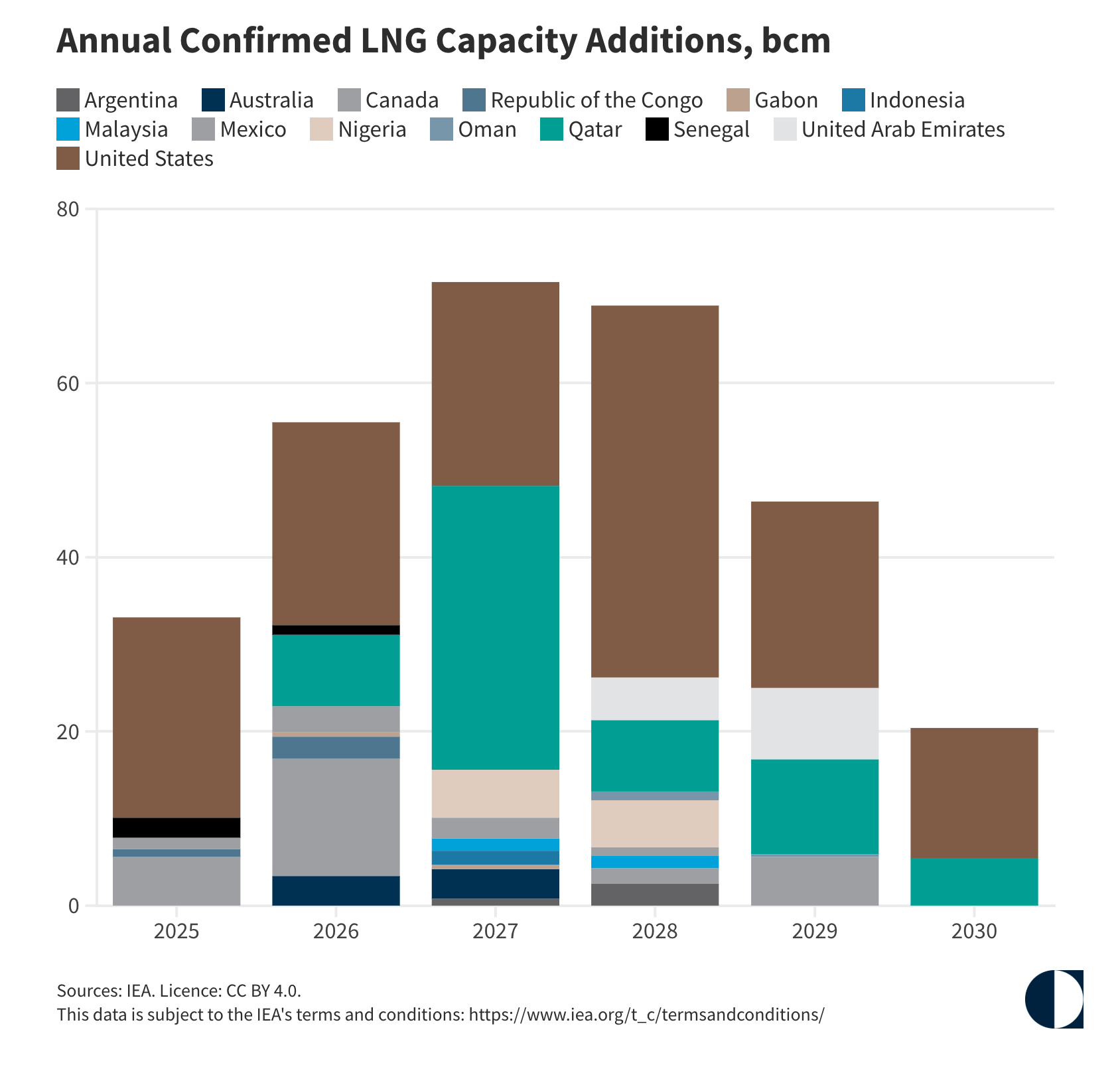

While LNG production in Russia and Qatar will either remain at current levels or grow, production in Malaysia and Australia looks set to fall. There might be additional large, yet-to-come-online LNG projects in Mozambique and Tanzania to tap, but they would not be sufficient to meet China’s import needs.

Global LNG production capacity is expected to grow by almost 300 billion cubic meters a year by 2030 but the geographical spread is a problem for China. “About half of the new capacity will come from the United States, 20 percent from Qatar, and 10 percent from Canada.” Vakulenko said. “But China can hardly count on the United States to supply it with LNG,” due to rising political tensions over Taiwan and broader strategic competition.

“The fact that almost all major international LNG projects involve companies headquartered in the United States or other NATO countries is also a problem for Beijing,” says Vakulenko.

In 2021, the US and Qatar were China’s top LNG suppliers, but by 2024 the US dropped to fourth place with just a 5% share. “The last LNG carrier headed for China left the United States in November 2024 and there have been no new cargoes since then,” Vakulenko said. “The current standoff is likely to be more serious and last longer” than previous trade disputes.

China has also signalled growing confidence in asserting energy independence. “Beijing’s decision in 2025 to accept LNG cargoes from the sanctioned Russian project Arctic LNG 2 should be understood in this context,” Vakulenko said.

Even though Russia has huge supplies of cheap gas and Beijing and Moscow have entered into a “no limits” partnership, China has had a long standing policy that no single exporter of critical natural resources should enjoy an excessively large slice of the Chinese market and Russia’s market share is already significant.

Pipeline deliveries from Russia stand at 38 billion cubic meters of gas per year, but they are poised to grow to 56 billion cubic meters (including up to 44 billion cubic meters via the Power of Siberia 1 pipeline, and as much as 12 billion cubic meters from gas production on Sakhalin). In addition to that, of course, China also receives large quantities of Russian LNG. The mooted Power of Siberia 2 (POS2) is planned to deliver an extra 50bcm if it ever gets built.

“If exports of Russian pipeline gas reach the volumes promised in recent statements about Power of Siberia 2, Russia’s share of China’s growing import portfolio will be 27–36 percent. Russia would account for 16–17.6 percent of China’s total gas consumption. Those are significant numbers—but not excessively so,” says Vakulenko.

The price of the gas will also play a key role and that part of the deal has yet to be agreed.

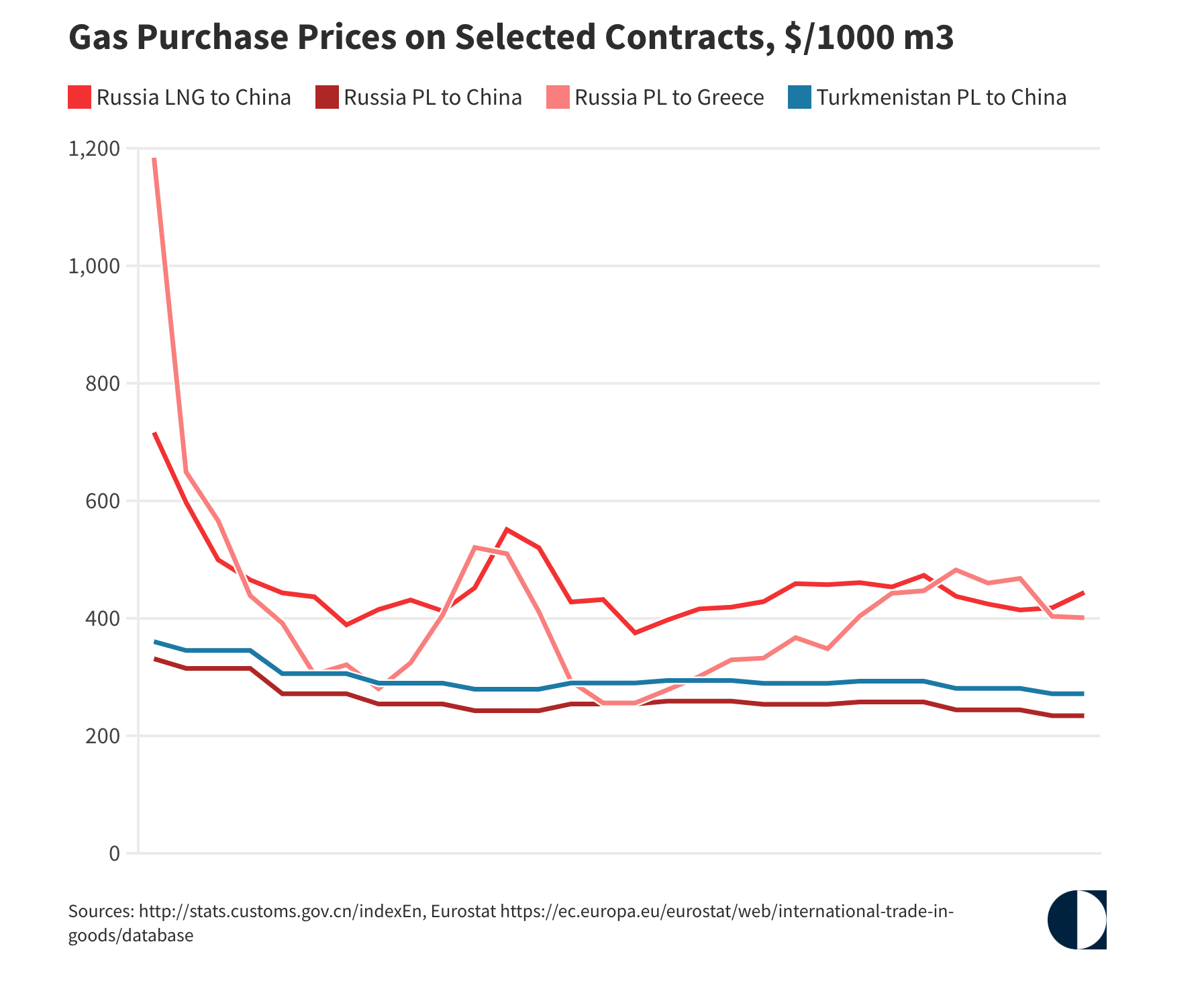

“For Russia, the breakeven price at the Chinese border is about $125 per thousand cubic meters. For China, the alternative to Russian pipeline gas is LNG, which currently costs an average of $370 per thousand cubic meters. That leaves a wide margin for negotiation,” says Vakulenko.

Russia did a bad deal when it signed off on the pricing formula on Power of Siberia 1 (PoS1); Turkmenistan, for example, sells gas to China using a pricing formula similar to Russia’s, but the price is $50 higher for every thousand cubic meters. This time around, Moscow likely wants to rectify past mistakes and negotiate terms at least comparable to those enjoyed by Central Asian states, which is holding up progress on signing off on a final deal.

Having lost its European gas business, Russia goes into the talks in a much weaker position, however, as Moscow has already agreed to pay for the construction of the POS2 pipeline, it’s in Russia’s interest to demand a long contract with minimum flexibility.

The commercial lifespan of Power of Siberia 2 is also important. If there is certainty it will still be generating revenue in a quarter of a century, current payments do not have to be too high, but the more uncertainty there is the higher the initial prices will have to be.

Thanks to its long-term planning, Beijing has a fairly clear idea of its energy needs over the next 15-20 years, but after that things are less certain and will be affected by the growth of its expanding renewable energy base.

Russia does not have any alternative and the negotiations are slow and difficult as Beijing pushes Moscow to see what it can get away with on price.

Unlock premium news, Start your free trial today.